Patricia A. McKillip is an evenement in fantasy. She writes neither fairytales-retellings nor epic fantasy. She never precises whether her books are for Young Adults or for adults, or for everybody. She doesn’t step into writing big multi-volumed sagas and her books aren’t centered on generic adventures or YA-ish finding of a True Lover. Her works aren’t typical but they are acclaimed, and I think they are so deservedly. And although they are no retellings of the classical fairy tales, they are closer to the definition of a retelling than most of the “dark” interpretations of Snow White or Cinderella.

There is everything a retelling requires in every book of her I’ve read—the twisted fairy logic of vows and promises, the mythical creatures, the riddles, the mystery, the unobviously ambiguous characters. And it isn’t the grim ambiguity of ASoIaF or LittleSiren-DeadlyKiller by Alexandra Christo and other YA authors of retellings. It’s something much more subtle. Patricia A. McKillip creates her own myths and fairy tales, and she creates them in an enchanting way. She uses the well-known tropes like ordinary things turning magical, dragons guarding treasures or wizards casting illusions. Her books are filled with brave kings and evil sorceresses, but the kings come out not to be so brave and the sorceresses not so sinister. And the best thing about the shifts she does and the illusions she reveals is that her tropes and narrative tools do not scream: It’s retelling!!! The paradox is that sometimes, it makes her stories more unobvious and progressive from all those books yelling “Look, I did representation/girl power/reinterpretation!”

And it works on many levels.

Let’s take, for example, the question of women and their sexuality in her books.

From the trilogy about the Riddlemaster, through The Cygnet and Alphabet of Thorn to Od Magic, her heroines (either on the first or the second stage, either in the legends or in the times of the very action) live in informal relationships, have lovers and bear kids out of wedlock. And it’s amazing on several levels.

The first thing, of course, is that all those plots and threads are subtle. McKillip yells neither “Look how liberated my women characters are!” nor “Look at those shameless sluts!”. Sex, parenting and falling in love are something perfectly normal and neutral in her worlds.

The second one is that those women (and men too, don’t worry) aren’t defined by their sexual life. Her female characters could be librarians, witches, rulers, warriors, can be positive or ambiguous characters, and all this has nothing to do with their love or sexual affairs. To me, it’s wonderful, really. I wonder whether is any other fantasy author as genuine as McKillip—writing, for example, about a woman who has three kids-out of-wedlock with three dads and who is a competent ruler whose descriptions aren’t sensual at all. Guy Gavriel Kay would write such a character too sexually. Robin Hobb—well, she would repeat probably something like “It’s a different culture but never take somebody so disgraced for your role model!”

Patricia A. McKillip is unique. Yeah. Just as her overall handling of the female characters.

There were things which irritated me at the beginning, I must confess. The trilogy about the Riddlemaster harboured some stereotypes, such as girls tending mostly to the household and princesses being cherished as valuable brides mainly, or a male-centered university. Even in this trilogy, though—published in the 1970s, remember—were introduced not only both female warriors and magicians, but the main female character came out to be a powerful sorceress with agency of her own, too.

Over the course of following—and usually standalone—novels Patricia A. McKillip got only better and better with the portrayal of her female characters, from their personality to introducing some elements of herstory.

In Od Magic, the figure of a sage and a mentor—a local Gandalf, you know—is an elderly female. And a famed magician is a girl pretending being her own father. In Alphabet of Thorn, it comes out that the first king of the land was actually the queen, which gives self-efficience to the young princess. Meanwhile, the main character discovers that her mother was a time-travelling sorceress cooperating with her cousin and lover, a greedy emperor. In Ombria in Shadow, both the antagonist and the protagonists are females—including an ambiguous witch who works for the Good Side eventually. In The Tower at Stony Wood, two shapechanging women work against the proud king who seems all a Noble Guy to the male protagonist.

The Tower at Stony Wood was the first McKillip’s book which made me discover author’s modus operandi, additionally. I realized that in her books, nothing is as the reader initially suppose. Bad witches—so hated in the patriarchal imaginary—turn friendly, shapechangers are not dangerous unhuman creatures, noble kings are flawed, women rejecting loving men are not Ungrateful Bitches. The most surprising message about The Tower… is the social one, though. Because this book (unlike Robin Hobb’s or Tolkien’s, hah!) isn’t about feudal loyality and keeping the establishment. It’s about the opposite, actually, and it isn’t the only McKillip’s book like that.

In Od Magic, the main character, a common-born mage-gardener, defies the stiff order of the magical school. In The Sorceress and the Cygnet, Corleu, a boy from a down-trodden tribe of wanderers, challanges the very gods.

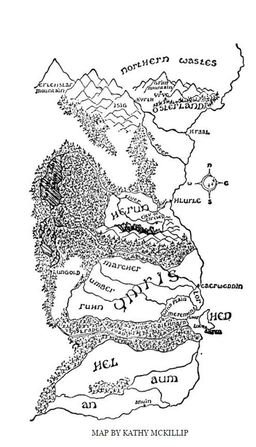

What I mean is that you shouldn’t judge Patricia A. McKillip’s books as a typical fantasy from white-cishetero-males era. Because her books aren’t like that at all—in every respect. Not only her female characters are numerous and well-described; people of colour are introduced as well. In the Riddlemaster trilogy, Morgon, the main character, could be interpreted as non-white. And there is the whole nation of Herun where the people are of colour. And all this is shown in a very natural way, deprived both of nasty racial stereotypes and virtue calling.

In her following books, non-white characters are introduced as well: in The Alphabet of Thorn and in The Cygnet they are protagonists, actually.

The eventual queer treads aren’t so obvious in McKillip’s writing, though. One may read the relation between Morgon and the High One as not entirely normative, and so the love- friendship between the dragon prince and his sorcerer in The Cygnet. However, nothing is proven. Please also remember that I’ve read only nine books of her, so I can’t judge them all. I can only hope that a writer whose worlds are so unobvious omitted some questions not out of homophobia. Not everybody is Mercedes Lackey.

And not everybody is Patricia A. McKillip, writing things which have been always progressive and subversive, and not being accused of introducing any political agenda at once.

I’ve only read Ombria in Shadow, but I am eager to read some of her other works! I’m excited to learn what more I have to look forward to.

LikeLike

Well, I encourage you to read on:). They’re simply good books.

LikeLiked by 1 person