The Sarantine Mosaic, consisting of Sailing to Sarantium and Lord of Emperors, is quite a paradoxical experience in my reading life, and in my adventure with GGK’s books. I find this duology his best work, even though as a feminist and as a socialist, I wish that some characters and events had been described differently. However, judging it as a work of literature, it is just better at its style, motives and pace than all the other books of Guy Gavriel Kay. I wish that such a book had been written about real Byzantium. Then, I suppose, it would be much more popular period in our pop culture. It is just… Well, never have I read such a good evocation of ancient Mediterranean world in fantasy. It is not only original in comparison to generic Medieval-like settings. It is original and just well-written in comparison to historical novels, too.

The Small and Great History of Commonfolk

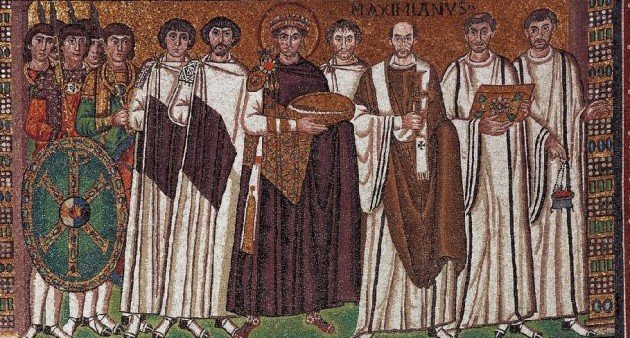

In this book, Guy Gavriel Kay makes something unusual in the genre. He introduces a main character who is low-born, who is a craftsman, an artisan, a mosaic-maker. He’s called Caius Crispus (Crispin), he’s past his thirties, and he lost his wife and his two daughters during the epidemy of plague. Do you think that he’ll end as a Chosen One/an aristocrat/an influential politician/a mage? Do you think that he has actually some special or aristocratic origins? No. And really, you don’t even know how happy I’m with this. Just compare it with The Farseer Trilogy. Or with Belgariad. Or with Frodo Baggins. No. His role will be mainly observing, and his influence subtle, and his work the theme which will remain very important through the both books. Mosaics aren’t only a pretext of evoking the ancient art or introducing an “artistic” character. They bring with themselves the symbols and hidden meanings, and the parallels of perceiving the art by the politicians. They’ll become the symbol of forgotten pagan beliefs with their soul-transporting dolphins and dangerous zubirs, and of the importance of daily life with the dead family of Crispin. They’ll become the symbol of pre-Christian-like wildness and roughness transported into the first images of sun god Jad, coarse and breath-taking, which will be the main inspiration for Crispin. And, above all, he‘ll remain an artist, SPOILERS making art for art, even knowing it will be destroyed. This is his rebel against the mighty of this world: the very memory, the very effort. SPOILERS

And he isn’t the only artist of the book. Guy Gavriel Kay, against the prejudices of stiff world, shows us that the cooking, the chariot-racing, the dancing, the medicine, could also be an art. All which is important is a concept and the skillfullness. And he allows to speak not only the masters of a craft or the famous racers; his story includes the voices of apprentices, cooking boys, physicians’ sons, beginning racers. They are allowed to be moved by art, to express their opinions, to experience joy and love as much as the more wealthy or more educated characters.

And even the wealthy or influential characters aren’t all well-born. The well-born characters aren’t even the majority in these books, anyway. The Emperor Valerius I is actually a peasant’s son from local Greece Trakesia, and Petrus his nephew begins his career to become his heir then, the Emperor Valerius II. His concubine, and then his beloved wife, Aliana, is a dancer of a chariot-racers’ fraction, an orphaned poor girl who grew into a woman of uncertain reputation. And guess what? All that is actually based almost literally on the lives of Justinian and Theodora, including even some quotes and political events. These allusions and historical references — or rather, finding them — is just a pleasure. I would say that this is the most historical novel of GGK, where parallels are obvious and yet — just tasty for anybody interested in history. And this history isn’t only about gilded domes and rich clothes; it is the history of cuisine and craft, of people still trying to make fine art in the post-apocalyptic times of fallen Roman-like empire, in the times of plague and war. And this time, there is nothing glorious in the war, there are only political intrigues and, as usual, afflicted commoners. And the theme of plague and the overall poverty in Italy-like Batiara is a striking contrast to the riches of Sarantium, and a good symbol of the times of change and unrest, when the Batiarans are merging with their German-like invaders of Antae tribe.

Maybe the most significant parallel to the sixth-century history is the Sarantine uprising based on the Nika riots. It tells us a lot about the way in which GGK portraits quasi-historical events and perceives the commonfolk in this duology. For his look is sober and realist, and yet by no means classist.

On the one hand, The Sarantine Mosaic doesn’t perpetuate the myth of Solidary Commonfolk. Aliana, although born into poor family, isn’t going to give up her power. She is even more ruthless than Petrus-Valerius, prompting him to use the army against the protesting commoners. And for me, this portrayal isn’t classist. It just shows how much the people cling to power.

On the other hand, the riots show us how much people who aren’t given the opportunity of decent life and education could be manipulated. The people who would make the most of it are of course the opponents of Valerius, not any common people. And these people demand just another imperator, not even imaging the possibility of the other form of governing. Even their frustration and demands are connected with the boundaries of their world. The world where a tax collector could be a paedophile and a murderer, and nobody cares because he is privileged, and where the teenage girls are already prostitutes.

Maybe this isn’t an entirely socialist perspective; the true is that GGK leaves numerous things without comments, giving the reader the right to one’s own interpretation. But he doesn’t portray his world as harmonic and just either, and such an approach towards social hierarchy isn’t conservative for sure. What is more, he deconstructs and mocks this world constantly. Empress Aliana doesn’t resemble an empress anymore, being dirty and exhausted. A revered senator has affairs with much younger boy-dancers (although I think that the trope of Loveless Gay fucking around much younger men discreetly is just irritating and harming). Impeccable matrons meet with Scortius, a famous low-born chariot racer. An imperial courtier is a drunkard afflicted with veneric disease. And over all this, there is a spirit of ribald, popular mockery, making the laugh the best weapon against the rich and the privileged ones. It isn’t only the historical realism from The Lions of Al-Rassan. It is the approach from the commonfolk’s perspective which would be probable and possible for the people from late Antiquity.

The Portrayal of Women

I’ve noticed that some reviewers on Goodreads find female characters of The Sarantine Mosaic cliched and portrayed unfairly. Some of them literally point out that in Sailing to Sarantium, almost all women are prostitutes or ex-prostitutes. To an extent, it is true, as the main female characters are: Aliana-Alixana (once a dancer), Shirin (a dancer), Kasia (an inn prostitute-slave from Sauradia province), Gisel (the queen of the Antae) and Styliane Daleina (an aristocrat from the house once plotting against Valerius II). As you may except, the first three women are or were considered prostitutes. Later, the two wives of Rustem the physician (from quasi-Persian Bassania) and the wife of our Secret Gay Plautus Bonosus will also appear. This time, we don’t have any female physician or artist (in the way of Lisette from A Song for Arbonne), and female warriors will be introduced into the newer books of GGK. So, does it mean that this duology is sexist or justyfying patriarchy? Surprisingly, not, and let me explain, why.

At first, in Sailing to Sarantium Guy Gavriel Kay finally understood something. He introduces a prostitute who is neither content nor really reconciled with her work. Kasia is petrified and hates paid sex. She endures rape and abuse, and she dreams of being free from her humiliating work. And all that is described so convicingly that becomes only more terryfying for the reader. Kasia endures rape and harassment, because she tries to survive in the dangerous land, far from her tribe and kin. SPOILERS But she couldn’t endure the thought of being sacrificed in the bloody local ritual, and so she asks travelling Crispus for help. They manage to escape, and their travel is a theme for completely different section of this essay. Kasia gets free and in Sarantium, she marries a decent and loving, but quite ill-mannered soldier whom she met already in the wildlands of Sauradia. SPOILER And, of course, I have one main problem with her plot. Although we are repeated how intelligent she is, she ends just as someone’s wife without no incomes of her own. It was typical for the Antique world, and her husband is at least no rapist or abuser, and yet the end of Kasia’s story seems just insufficient for me. GGK’s female characters usually have various goals, and a marriage could be, but doesn’t need to be one of them. However, her plot still has more good than bad points, and noticing the hardships of sexual worker’s life is of course the good one. What is more, there is one sex scene between Kasia and Crispin, and it is by no means sexist, pointless or creepy. The scene isn’t about selling your body again, this time to a man to whom you’re grateful. This scene is about regaining your sexual identity. Kasia couldn’t remember sex as something good and pleasant. And Crispin shows her that it can be otherwise, treating her tenderly and cautiously, giving her pleasure. It is a healing experience.

As in the Kasia’s case GGK just gives justice to harassed and abused women, he overthrows some stereotypes describing the next two characters: Aliana and Styliane. And the case of Aliana is maybe even more important than some particular Styliane’s plot. Her story subverts many tropes typical for both historical fiction and for the stories of childless marriages. Aliana had an abortion as a girl, but she still could have children; it is Valerius who is infertile. I was so glad reading this trope… At first, there is no thread of punishing a woman with infertility because of an abortion (which I’ve found in A Secret History of Witches for example, a book very sceptic about Catholic Church, but strangely conservative when it comes to the reproductive health). At second, do you remember all these historical queens accused of infertility? And do you remember Patience from The Farseer Trilogy? Here, at last, there is a very nice subversion of The Infertile Queen trope. SPOILERS What is more, at the end of the duology, Aliana anonymously finds Crispin in Varena/Ravenna (as Valerius was killed). They realize they love each other, and there is quite a sweet reference to an eventual child they are planning. I love the solution of their plot, because this is just original as for the fantasy standards. They are both widowed, they are no longer young, and Aliana is slightly older from Crispin. For me, they make just a sweet couple, especially that their encounters are based on a friendship at first. And the whole plot is resolved in such a way that we don’t feel that Aliana forgets her husband. No, it was a great and unusual relationship, but something had been just ended. For Aliana, there is no return to the royal life, and for Crispin -– to observe the great politics. And so they enjoy the live they could have, and they suit together perfectly. SPOILERS

And well, Aliana is just a cunning and likeable character, anyway. We support her because she was born as a commoner — like the most of us — and because she has become Valerius’ wife against all the social conventions. She suits into the famous trope of equally Famous and Forbidden Love, and she has all the makings of a Powerful Woman, too. Sometimes she is even more ruthless than Valerius, and she remains his political partner. She has her secret intrigues, and he trusts her and asks her for advice. It’s clear that they are not only lovers, but friends, too. And their marital friendship subverts the trope of relation with a mistress or a prostitute (ex or not) based mainly on sex. They are partners, they are faithful and friendly towards each other, and the very portrayal of their relationship make the character of Valerius lovable for me. It reminds me of The General in His Labyrinth (too much associations again, damn!), but Valerius is even better, as a faithful chap.

But supposedly the most subversive female character in the duology is Styliane Daleina. She isn’t like the most women in fiction, whose main goals are marriage, finding a True Love Man or some vaguely described “happiness”. Wait, wait… Do you think I’m turning sexist? Nope. The true is that women have numerous and vary goals, and that fiction is just stereotypizing them. In fiction, almost all things must be connected with men: women escaping from men, women seeking men, women following men… The reality has never been like that, and some tropes like “marriage vs solitude”, “family vs career” are just imposed on us by the patriarchy. Heterosexual woman can be happy without husband, or without men at all. A man may seek some quiet countryside life as much as a woman. You can have both children and a satisfying work (and a helpful father who is a TRUE parent instead of being a cash-point is quite helpful in this case). And, well, what does Styliane Daleina have in common with all this? Her goal isn’t any man or a peaceful life. Her goal is a revenge for her kin’s death, and she has been working on it for years. Of course, revenge is a cliched trope, but in Styliane’s case, GGK subverted it in several ways.

At first, we don’t learn about Styliane’s plans till the half of the second book. We see her as a proud and bored wife of commander Leontius, discreetly cheating on him. At best, we suspect another Arianne from A Song for Arbonne. At second, we already know that Styliane despises Valerius and Aliana, but we don’t suspect that she will go so far. We see some petty intrigues, but when it comes to Valerius’ death, we are as shocked as Caesar must have been seeing Brutus. And this time Brutus is a woman. As for the books published twenty years ago, it is original. At third, Styliane has all the matches of that avenger type which was supposed to suit only men for centuries. She is embittered, she hates Valerius, the revenge is her main life goal, and she has been planning her intrigue almost since her girlhood days. In man’s case, all these tropes would be too cliched or too classic, but in woman’s, they seem original. Because, you see, too few stories about women’s revenge has been told by our culture. And so the character of Styliane seems to be so fresh and original. I’m not stating that the revenge is a good literary trope. I’m not stating that making a belivable female character is about subverting women into vengeful men. I just think that this time, such subversion was both natural and original.

The portrayal of Gisel and Rustem’s two wives is another question, representing completelely two different tropes and tales.

Gisel is a woman aware of living in a patriarchal society. She knows she is endangered by the men plotting against her, and she knows which possibilities she has when it comes to defending herself. And so she offers herself to Valerius as a young and fertile would-be wife. And so, when it becomes clear that the emperor will always love Alixana, Gisel would take up with embittered Leontius, finding her first sexual intercourse as something painful and unpleasant. It is something very sad in all this. In my opinion, this time GGK doesn’t say “Who cares, it will always be so.” No. This time, the message is painful and bitter. Look at this woman. Look at Kasia. Look at the things the women had to endure in patriarchy. And we may not see this notion not because there is a hidden sexism in Gisel’s portrayal. We may not see it because all that is described in the way suiting an Antique-like character. Gisel just isn’t describing her experiences in the way a contemporary woman would.

Rustem’s wives are another type of characters. They are happy with their husband and their provincional life. SPOILERS And their life changes dramatically when Rustem, having saved king Shirvan, is sent to Sarantium. I can tell you only one thing: these woman are braver and more solidary than Rustem suspected. They would trick him excellently. SPOILERS I just like them because they are a good example of people from different culture who like their traditional life and who aren’t abused by it. It isn’t justyfying of women’s discrimination. It only means that one shoe doesn’t fit all.

The only female character problematic to me is Shirin. Sure, she is clever, charming, likeable, she gets hots for Crispin and then she becomes his BBF. But she seems perfectly content with her dancer-prostitute’s life. Unlike in Kasia’s case, GGK doesn’t see all the harassment and coercion which sex workers may endure. No, Shirin is happy and it seems she chooses her lovers freely. Well… I suppose I don’t need to explain you that such a vision is too optimistic?

Writing Technique

Maybe I like The Sarantine Mosaic the most of GGK’s books because it is just well written, written in a better way than all his other books I know.

It isn’t only the question of original GGK’s style, full of lyricism and evocative descriptions. This style is not only mature and deliberate in this duology; it is also influenced by some classical writers. Sometimes it seems to me that some passages, motives and ironic remarks might have been written and invented by Marquez or Allende as well. The story of Pronobius Tilliticus, a completely-unholy courier ending as a local saint and eremite, reminds me especially of typical magical realism’s retelling and irony. A drunker and a whoremonger then considered a saint -– it’s the level of the bishop’s mule performing miracles in The Love in the Times of Cholera! And all this described in truly Marquez-esque style, indeed.

And maybe this is the key of The Sarantine Mosaic’s mastery – that Guy Gavriel Kay picked up a more objective style from some modern classics. He doesn’t cease to use PoVs, but a more detached narration is an important part of these two books as well. And it makes the books only good. The whole perspective seems more epic and broader, almost historical, and the descriptions of imperial institutions and offices – more believable. It makes the duology outstanding not only among the fantasy genre, but among historical fiction, too. I wish Le Rois Maudits had been written in this technique! I wish Robin Hobb picked some of this style instead of writing lenghty tame-pathetic books. Because when GGK uses objective narration, it is neither dull nor stiff, but rich and fascinating.

Surprisingly, even his inclination to pathetic or “telling” descriptions, to highlighting crucial scenes and spoilering some events, seem more natural, being accompanied by more detached narration. They just suit into some historical novels’ tricks — like the awareness that the readers know how a character will end, so all the hows are more important than iffs. And this is why we know that Valerius will be murdered, but we learn it very soon before his death. This is why we learn what will happen to Plautus Bonosus’ son, or to Rustem and his descendants (Rodrigo from The Lions of Al-Rassan might be one of them, yay!). Such foreshadowings and premonitions are typical of course — again — for magical realism, too. And the paradox is that the awareness of one’s upcoming death makes some particular scenes only more poignant. Believe or not, I cried reading about Valerius’ death.

I wish only GGK wrote once a book about everyday life, to which this style would match perfectly. Because The Sarantine Mosaic — filled with descriptions of making mosaics, chariot-racing, weddings as it is — is still a book more about politics than about dailyness. It’s not a flaw, but it isn’t my wish-fullfilment, either. Treat it as the words of admiration – I consider GGK such a good writer that it would be very interesting to see a novel like Madame Bovary or Brideshead Revisited, or One Hundred Years of Solitude by him. As you see, the category is very broad.

Realism Even More Improved

The Sarantine Mosaic seems to be the golden mean between sobriety and vulgarity. Unlike ASoIaF, it isn’t overloaded with curses, violence for violence and pointless sex scenes. Unlike The Farseer Trilogy or The Belgariad, it is by no means naïve or turning into conservative wishful thinking in the matters of sex and relationships. Here not every love results in childbirth, and not all the lovers are in love actually. Here a revered senator is a hidden gay, here noble ladies are having trysts with chariot-racers. Here the emperor’s heir loves his mistress and a former prostitute at once so much, that he marries her against all the prejudices. If you are one of these conservatives thinking that “once upon a time there was no extramarital sex and LGBT people” you’d better pick up GGK’s books.

The Sarantine Mosaic is not a retelling in the way of The Mists of Avalon. It is as much deep into its own times and places as Decameron or Illusions Perdues were. The comparison isn’t coincidental – Balzac and Boccaccio are one of these writers which make us believe in the past not so different from our times, because they’ve been there, seen that. You can’t accuse them of being mythical cultural marxists lying about the past to overthrow so-called traditional values. Boccaccio, let’s say, was a Christian living in the times when officially everybody was a believer and a church-goer, when there were no of these terrible feminists and these immoral democratic values. And guess what? People still had premarital sex, still cheated on their spouses, teens still got pregnant, and… Gays existed, too! How shocking. *Ends her mockery*

The point is that The Sarantine Mosaic is just like Decameron or The Human Comedy. It seems to be a believable account of the private life in a particular epoch, not connected with any tries of “proving” something. It is the account natural and unobtrusive, and full of so many historical references that it is more believable than, let’s say, the myth of feminist Avalon.

The Sarantine Mosaic is very sober on other levels, as well, especially when it comes to the politics. It busts some myths about political intrigues (like the conviction that only fanatics support religious restrictions) and — at once — by no means whitewashes anybody. Valerius isn’t justified when it comes to pacyfying the riots or forbidding Heladikos (Jad’s son) cult, or accepting a creepy but effective tax collector. He is shown just as a political gamer who couldn’t afford himself being an idealist. And he is so because he finds some goals more important than others. He likes ancient philosophy and he is no fanatic, but he needs Holy Patriarch’s support, so he banes Heladikos’ cult. He wants to reclaim Batiara, so he pays the Bassanids for the peace on the east.

Realism applies not only to politics or human sexuality here, but to numerous details, big and small. The streets of Sarantium are dirty and crowded. Rich and poor people are dying from plague alike. The work of a waitress in a provincial inn is tough and full of abuse. People are swearing, gambling, cheating. And the best is that all the “dirty” things are portrayed very naturally, without any fetish of “OMG, look how the life is brutal!1!1!”.

The things which should be realistic in every novel, are, of course, characters. And I think that this time, GGK truly did his best. Most of characters are just believable. And even if some of them suit into archetypes, these archetypes aren’t the most obvious ones, or they are twisted on their heads. This applies to Styliane, a typical Avenger who is a woman, to Callidus the soldier, who is a Bawdy Coarse Guy, and yet he doesn’t meet all the cliches of such a type. He turns out to be a faithful and tender husband who doesn’t give Kasia many reasons to worry — unlike, let’s say, Robert Baratheon.

But the most important characters aren’t typically archetypical, and this is the best thing. Crispin, Valerius and Aliana are just complex like real human beings.

Crispin, as I’ve examined, isn’t a typical fantasy protagonist. Even his lost of the family isn’t fantasy-like at all — no hidden royal family’s assassination trope, no killing monsters or epic fail of a country. Crispin’s beloved are killed randomly and mercilessly by a thing very common in the old world – plague.

And he isn’t your stereotypical artist, either. He is neither a womanizer hard-to-live-with, nor an eccentric maniac. He tends to get angry, but he believes in his apprentices and he makes friends easily. And his love towards art isn’t presented as something enigmatic, but just as an integral and practical part of his life. All the descriptions of making mosaics sound not only believable in the book, but fascinating, too.

And, above all, he is likeable. He’s a commonfolk guy, a lonely widower, he has many good instincts towards harassed and abused people. He is a man with whom a reader could identify.

Valerius is another kind of character, full of paradoxes, which are shown even in his political actions. If he is likeable, than it is rather due to his private life. But, above all, he is just a complex and unobvious character – and even if one doesn’t like him, one still must admit that Valerius is very believable.

Assuming that I’ve examined most female characters before, I’d like to point out somebody else – Rustem the physician, which is another example of a paradoxical character. He is both a clever and talented physician, and a very superstitious man at once, sticking strictly to his manichean beliefs. He is also quite a tricky man, cheating on his wives, on his benefactors, and pretending he is older than he really is. And yet, he is quite likeable.

While Valerius and Alixana still seem to be human-like, there is a ruler portrayed as somebody distant, mighty and terryfying – Shirvan, the Great King of Bassanids. His personality reflects the eastern way of governing even more than rich clothes and pomptous obeisance at Valerius’ court. Shirvan seems to be omnipotent in his country — he kills his son for plotting against him, and he kills a doctor who didn’t manage to heal his wound. And yet he is the one who will fail under the conquest of the new desert faith of Ashar.

Religious and Historical References

One of the reasons I like The Sarantine Mosaic so much is that the ties with our world and our history are stronger, more deliberate and more accurate than in any of the other books of GGK. The duology is more a retelling of Justinian’s rules than anything else, more a historical than a fantasy novel.

I’ve already mentioned numerous parallels between Valerius/Justinian&Alixana/Theodora. However, the specific Byzantine-like atmosphere may be even more important than any historical references. Through some simple and memorable elements — the name, gilded domes, chariot races, Antiquity heritage, Mediterranean-like setting, the senate, royal couriers — GGK evoked Byzantium, choosing the most recognizable references. Some of them are delightful to any history-lovers, but some might remain unclear to an average reader, supposedly not an expert in the Byzantine history. The true is I have no clue on which tribe the Sauradian Inicii were based, or which was the prototype of the Jad’s mosaic in the dilapidated Sauradian sanctuary. But, on the other hand, I enjoyed a lot Pertennius’ character, having learnt about Procopius of Caesarea and his attitude towards Theodora.

Italy-like Batiara and Balcanic-like Sauradia also seem believable, and when one might be dissapointed by the very straight-forward historical references (Ravenna/Varena, and Crispin’s mosaic in San Vitale, of course!, and Rome/Rhodias) I don’t have anything against them, personally. I think (or I hope) that they are deliberate, like the contrast between Sauradian wilderness and Batiaran cities, like the contrast between manichean Jad and Bassanid gods (Azor Ahai Ahura Mazda sends his greetings) and between older and wilder zubir. Because every culture depicted in the duology has to remind us of something, including waking Asharites (damn, even the timing is good, in comparison to 622 AD and the timeline of Justinian). And if some events are different (Valerius/Justinian murdered, Sarantium reclaiming Batiara through the altar diplomacy) it is also on a purpose. These shiftings can show us different possibilities and different strains, a new look into the real history.

How religion is depicted in the books is another question. It is the picture based on the contrast – Jaddite and pagan, new and old, absolutism and relativism. It is something very wise and mature in it — to show different religions without appeal to any of them, to show both the intolerance of Jaddites and the cruelty of some older cults, to show struggles between religious fractions and pagan beliefs, which aren’t — and never will be — gone for ever. And there is the mysterious pagan magic, a magic which both could give and take. The obvious symbols of this magic are talking birds of Zoticus, a dubious neighbour of Crispin, an old mage. SPOILERS The birds which were brought to live by the souls of the girls murdered in a sacriface to zubir. And one of these birds zubir will reclaim again on the mysterious, misty Sauradian road, as a pay for Crispin’s and his companions safety (and this plot is one of the most exciting and terryfying ones in Sailing to Sarantium). And he reclaim Zoticus, too, for there must be a pay for the magic – life for life and soul for soul. SPOILERS

However, it doesn’t mean that GGK shows paganism as something cruel and terrible. Zubir — and an old, coarse image of Jad on the old mosaic — is only one side of it. There is ancient Trakesian philosophy, more nuanced and sophisticated than Jaddite beliefs – a symbol of ancient way of thinking and living which is fading away. A symbol of the antique subtlety which would remain forgotten – in our world and in the Jadiverse – for the next several centuries. There are dolphins, the forbidden symbols of soul-transporters to the otherworld, and maybe the symbol of the nature, so much closer to the ancient gods than to the solar Jad. And there is Heladikos, a figure both Jesus-like and promethean, the light-bringer, the son of Jad which soon will be forbidden, too.

Because this is the story of some end. The end of some times, of religious and philosphical diversity, of bright Mediterranean-centered world.

So… Is anything wrong here?

Of course it is😁 But still, this duology is so deliberate and well-written in comparison to most fantasy books — and to the rest of the GGK’s books — that for me, all its advantages are more important than several drawbacks. Which, to my nitpicky mind, are:

– a pointless sex scene between Styliane and Crispin;

– lack of any woman character who would be a healer/tradeswoman/craftswoman/whatever;

– reminding the readers that This scene is important. However, as I’ve mentioned before, with a hint of magical realism-like style it isn’t as irritating as before;

– Shirin’s life still seems too nice and easy.;

– Heladikos’ references, which still are more promethean than anything else, and doesn’t reflect well the differences between the Western and the Eastern Church, and between the Ostrogothic Arian Christianity and the Catholicism;

– that we don’t know what happened next to Scortius and the rest of the chariot staff, learning at once about the later life of Plautus Bonosus’ son and Rustem’ family. What a pity!;

– another heartless gay interested only in sex is just a harming stereotype

And that would be all. I’m afraid that The Last Light of the Sun won’t be reviewed here, assuming that I don’t have the book in paper, and I can’t recall it properly. So, the next time, prepare for the return to Batiara, and to probably the beloved GGK’s setting — Renaissance Italy-like land.